Steven Bartlett’s book, Happy, Sexy Millionaire, is part memoir and part self-help. I’m a long-time fan of Bartlett’s podcast, the Diary of a CEO podcast, and this book first turned me onto his work.

Introduction

- Bartlett writes, “The reason I aspired to be a sexy millionaire is ultimately because I believed that would make me happy” (2). We all want to be happy.

- The goal of the book is to “suck all of the bullshit social brainwashing out of your mind and replace it with a practical, scientifically proven set of unconventional ideas that will help you find the fulfillment, love, and success that we’re all craving and searching for” (3).

- The words “happy,” “sexy,” and “millionaire” are proxies for bigger ideas we have a hard time wrapping our heads around.

- “Happy” is not a mood. Instead, Bartlett defines it as “an internal feeling of fulfillment” (4). Thus, you can experience a fleeting mood, like anger, and still be happy and fulfilled overall.

- “Sexy” is a proxy for being loveable and loved. Few people want to be sexually attractive for its own sake, instead we “desire to form romantic relationships and the value that a partner can have in our lives” (5).

- “Millionaire” is a proxy for success. Bartlett writes, “Becoming a ‘millionaire’ is seen as a cultural benchmark and measure of ‘success’… Success is a subjective concept based on what you aim for and determined by what matters to you” (5).

- In short, “this book is about fulfillment, love and success,” not being a “happy, sexy millionaire” (5).

Chapter Two

- In life, there are two types of games: infinite games and finite games. Bartlett describes both:

- “A finite game is played for the purpose of winning and therefore ending the game, like football, bingo, or poker…” (12)

- “An infinite game… is designed for the purpose of continuing the play. There are no winners or losers—just an ongoing experience. There is only one infinite game: our lives” (12).

- James Carse’s book, Finite and Infinite Games, inspired Bartlett here and expands on this philosophical position.

- Problems arise when people try to play the infinite game (life) like its a finite game. You cannot “win” at being happy. You can only “be” it (12).

- Expanding on his lifeview, Bartlett writes, “It’s a perpetual ongoing infinite experience that only ceases when you die…You have to play it without expectation of a finish line…and without what I call a ‘destination mindset'” (14).

- “Believe it or note, the liberating and therapeutic truth is that you are already enough” (14). That’s a nice sentiment, but it never sits well when someone ends the discussion there. Thankfully, Bartlett follows up with the questions that always come to mind after hearing “you’re already enough.” He writes,

- “What is the point in life then?” (14)

- “If I don’t have any progress to make, or anything to prove, then why get out of bed in the morning?” (14).

- “This is one of the great paradoxes of happiness: you have to call off the search in order to find everything you’ve been searching for” (16).

- Discussing self-worth and the transformational therapist Marisa Peer, Bartlett writes a paragraph worth quoting at length:

- “When someone knows they’re enough, they don’t lie around doing nothing — in fact, you see the opposite reaction. Knowing you’re enough is the realization of your own worth — which drives people to strive for things even greater than their current circumstance. It’s the difference between feeling you need something (often to satisfy an insecurity) and feeling you deserve something (to satisfy your sense of self-worth and your own ability)” (14).

- The feeling of not being enough is an outcome of social brainwashing (16), driven by the motives of others. Bartlett asks a series of illuminating questions,

- “How can corporations sell you shit you don’t need if they don’t first convince you that there is something you don’t have?” (18)

- “How can schools and universities inspire you to work hard and climb the corporate ladder if they don’t first convince you that there is something up there worth climbing to?” (18)

- “The narrative that I had chosen to believe — that I was missing something — was the thing causing my unhappiness” (18).

- “In a zero-sum game, you can only gain something by taking it off another person” (18). This concept is grounded in scarcity.

Chapter Three

- “Our brains are designed to be incapable of constant rational thought — we simply don’t have the time or mental capacity to calculate the statistical probabilities and potential risks that come with the tens of thousands of choices we make ever day…” (22)

- Cf. Kahneman. Thinking, Fast and Slow.

- Cf. Schwartz. The Paradox of Choice.

- “Scientific studies show that the choice your mental CEO will make can differ, even when the facts at hand don’t change” (23).

- “We determine the value of things relative to the circumstances rather than in absolute and logical terms” (23).

- “The truth is that nothing in life has any intrinsic value without context” (23).

- “In the context of the social-media oriented world we live in, this approach will inescapably present everyone as being apparently prettier, apparently stronger, apparently sexier, apparently happier, and apparently more successful than you, and will almost certainly make you unsatisfied at best” (24).

- “The only worthwhile comparison is YOU yesterday vs YOU today. If you want to be happy, you have to focus on that” (26).

Chapter Four

- “You won’t stop comparing yourself to others regardless of what I say because you won’t stop being human” (27). Therefore, the popular advice to “don’t give a fuck” is fundamentally flawed in the context of human nature. Also, “don’t let it get to you” is useless advice. You’re human. Shit is going to get to you and you will give a fuck. Given that, how do you handle yourself?

- “You wouldn’t continue to read books that told you you’re a worthless, ugly, unsuccessful piece of shit, so why have you chosen to fill a digital library with content that will evidently do the same?” (29)

- “You are by any logical definition unique, so any comparison is inherently and logically unfair” (30).

- “Make your context smaller, healthier and more real” (32).

Chapter Five

- “If a person could do only one simple thing to increase their health and happiness then expressing gratitude on a regular basis must be it” (37).

- “Gratitude isn’t an approach centered on removing your lazy CEO from office — as I said that isn’t possible — it’s one that focuses on giving your CEO additional healthier responsibilities — better context — that will help you to create a more positive self-assessment of how ‘complete’ you are” (39).

- “Social media has given all of us an endless and unrealistic context in which to compare ourselves to others, and although we can’t easily change our prehistoric wiring, we can subdue its power over us by being more consciously aware of what’s happening, what’s causing it, and the impact is has on us” (40).

- “If you go through life believing that happiness is somewhere in your future, it always will be — it will never be where you are now” (42).

- “Live in accordance with your outside world and you’ll soon find misery. Live in accordance with your inside world and you’ll soon find happiness” (44).

- “Maybe I wouldn’t have felt so much inadequacy and the need to become a sexy millionaire if I was able to be a little more grateful when I was younger” (48).

- “Cumulatively, the research agrees that contributing to a gratitude journal at any frequency between once a day to once a week had substantial positive effects on well-being” (48).

- “I realize that I can’t ever become the richest, prettiest, or the smartest… So I know that I…must ardently reject the desire to embark on any such journey, and endeavor instead to focus the saved time and energy on being grateful now” (53).

Chapter Six

- “I can’t think of many things that have done more damage to the mental peace of this connected generation than the socially propagated fairy tales about how our lives are supposed to be going” (56).

- “The truth that I’ve unmistakably witnessed in my own life is that achieving all of our goals is what ultimately leads to chaos and dissatisfaction — wheras the state of striving actually provides us with stability and satisfaction” (57).

- This is because “an accomplished goal brings with it a loss of orientation and the risk of being swayed towards the chaos of purposelessness and psychological destabilization” (57).

- “The Stoics considered two things in life worth pursuing,” (59)

- Virtue: how we live happy lives.

- Tranquility: a lucid state characterized by ongoing freedom from distress.

- To overcome the hedonic treadmill, Bartlett recounts two Stoic exercises:

- Negative Visualization: “For an idea of how negative visualization works, imagine that the things and people you take for granted, like family or close friends, suddenly vanish. The feeling of loss is awful” (59).

- Voluntary Discomfort: “Abstaining from something so that you can truly appreciate the value of it when you gain access to it again” (61).

- Referencing Plato, Bartlett says, “The secret of happiness, you see, is not found in seeking more, but in developing the capacity to enjoy less” (61).

- Bartlett uses a discussion of abs to convey an interesting value theory. He writes, “The social value of having a six-pack is pretty remarkable. But have you ever really considered why? […] Abs take tremendous discipline, strength and hard work… Therefore, part of the value of anything lives not in the thing, but in the story of all of the things you said no to in order to have it… Maybe self-restraint is the thing that makes things feel so precious” (61-62).

- “There is a fundamental limit to how many balls you’re able to juggle… The foolish endeavor to juggle them all will only result in failure” (63).

Chapter Seven

- “Because society makes everything look perfect and binary, imperfect and complex feel wrong. Life is imperfect and complex, but life isn’t wrong” (67).

- Jabbing against the popular “follow your passion” advice, Bartlett writes, “The truth is, people have multiple ‘passions’; they’re fluid and evolve with age, wisdom and experience” (69).

- Cf. Margaret Lobenstine’s The Renaissance Soul. A good book on having many passions in life and pursuing them; sometimes sequentially and sometimes simultaneously.

Chapter Eight

- “There is no script for life… My ability to resist conforming to the script, to resist trying to squeeze into society’s binary boxes or answer invalid questions and write fresh rules for how my life will be lived is unquestionably much of the reason I found success and happiness in the way I did” (71).

- “I’m okay with the idea that my experience is an extremely individual, ever-evolving, somewhat indescribable one” (73).

- “It isn’t the accomplishment of society’s expectations that will make you happiest, it’s the rejection of them” (75).

Chapter Nine

- “Intrinsically motivating work makes people a lot happier than a big [paycheck]” (77).

- “Scientists have shown that we’re actually really bad at forecasting what will make us happy, and we don’t even realize how useless we are at this” (78).

- “Having demands that drastically exceed your abilities and level of competence is overwhelming and does cause harmful stress but having a very undemanding job can be deeply unrewarding too. The sweet spot is where the demands placed on you match your actual abilities and your self-perceived abilities — that makes for a fulfilling challenge” (79).

- An interesting task as a manager will be recognizing how much demand you can place of specific employees with overwhelming them or boring them.

- “People who exercise patience and self-restraint over long periods of time, who work towards a worthwhile goal without short-cuts or instant gratification, attain more happiness and success in the long term” (81).

- Bartlett outlines “five crucial elements to a ‘dream job,’ ingredients that have been widely psychologically proven to increase human satisfaction” (81).

- “Engaging work is work that pulls you in, holds you, and enchants you” (81). There are four factors behind engaging work:

- “The freedom to decide how to perform your work.

- Clear tasks, with a clearly defined start and end.

- Variety in the types of task.

- Feedback — so you know how well you’re doing” (83).

- “Work that helps others” (83).

- “The psychological theory [behind ‘helper’s high’] is that giving and acts of kindness produce a natural mild version of a morphine high in the brain” (88).

- “There is no exercise better for the mind than reaching down and lifting another person up” (90).

- “Don’t just do what you love, do what you’re good at” (90).

- “Skill trumps interest… you should aim to pursue work you have the potential to get good at” (91).

- “Don’t work with arseholes” (92).

- “Perhaps the most important factor in job satisfaction is whether your boss and colleagues are supportive… A bad boss, selfish colleagues, or a toxic work culture can ruin a ‘dream’ role, whereas agreeable workmates can make even mundane work enjoyable” (92).

- “Work matters but so does the rest of life” (93). You need to find your work-life harmony.

- “Creating meaning and fulfilment is an individual, fluid and multidimensional endeavor that we must all approach differently” (93).

- You need to find harmony between your personal ambitions, your basic physiological needs, your psychological-esteem needs, and your need for love, connection, and belonging (93).

- “Engaging work is work that pulls you in, holds you, and enchants you” (81). There are four factors behind engaging work:

- “If you’re just in search of success or status, don’t aspire to be your hero; stop trying to impersonate what you see others doing… Learn from them and steal from them, but don’t try to be them” (86).

- “Career capital is anything that puts you in a better position to make a difference in your future career — such as skills, connections, qualifications, and resources” (90).

- “The earlier you are in your career, and the less certain you are about what to do in the medium-term, the more you should focus on gaining career capital that’s transferable to other sectors” (90).

- “I’m pouring as much value as I can into five key buckets that I will be able to leverage for life:

- What I know (knowledge)

- Who I know (network)

- What I’m able to do (my skills)

- What others think of me (reputation)

- What I have (my resources)” (90-91).

Chapter Ten

- “Silicon Valley has ‘optimized’ the life out of our lives” (97).

- “Our psychological needs are invisible (community, human connection, free movement, meaning, nature), so we continue to employ technology to optimize against them in the name of convenience, saving time, our physical needs, and becoming more ‘successful'” (97).

- “Clearly social networks arent that social, and an internet connection doesn’t guarantee human connection” (99).

- “My unrelenting internal monologue was fuelled by the ‘inspiration’ of online hustle pornstars and a toxic social media culture that glorifies anyome pretending to work really fucking hard or, conversely, anyone pretending to do the opposite. This reassured me that the harder I worked, the more stuff I would have, the richer I woukd become, the greater would be my status, the more women would like me and, therefore, the happier I would be. What an insecure, misguided man I was” (105).

- “I am not against hard work… I get tremendous fulfilment, stimulation, and joy from the work I do and the sense of accomplishment it brings me… The issue isn’t the hard work itself, it’s what you work hard at the expense of” (108).

Chapter Eleven

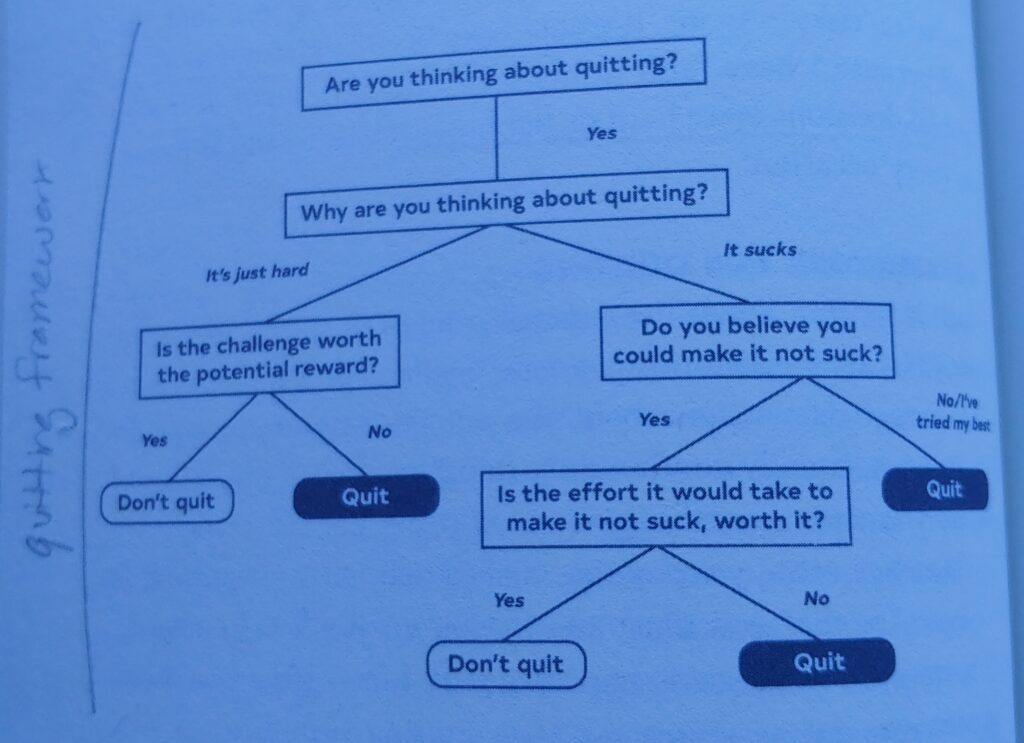

- “Quitting is for winners and quitting is a skill” (111).

- Cf. The Dip by …

- Cf. Essentialism by Greg McKeown.

- Bartlett’s Quitting Framework:

- “Every time I’ve quit, people have called me crazy… But every time, without fail, it’s led me to more fulfilment, better love, and higher success… I have never regretted a major quitting decision” (112).

- “My professional mission is to fill my life with difficult but worthwhile challenges” (113).

- “I do quit, though, because things suck, and I lose faith that I can stop them sucking and/or because the effort it would take to stop it sucking is no longer worth the reward on offer” (113).

- “This illuminated another important factor that prevents people quitting the wrong thing at the right time — the comfort-seeking need to have their next step perfectly figured out before they do so” (113). I have definitely fallen prey to that concern..

- Bartlett’s rebuttal to that concern: “I had no plan. I just had a lot of faith in myself and a lot of faith in the rationale underpinning my decision” (113). If your mind is sound and your rationale for quitting is sound, then just quit. Don’t worry about what comes next; you’ll figure it out.

- “I believe that the happiness you’ll find across areas of life — your work, your relationships, and everything im between — will positively correlate to your ability to deal with uncertainty” (115).

- “You are guaranteed to make bad choices until the day that you die, and that’s fine because that’s life” (117).

- “Uncertainty is the gap between your current miserable situation and an unknown happier position” (118).

- Bartlett had a conversation with Barack Obama about making big decisions. I’m gonna quote Obama’s words to Bartlett at length because they’re worth it.

- “I only dealt with the hard stuff. If it was an easy problem to solve, or even a moderately difficult but solvable problem, it would not reach me because, by definition, somebody else would have solved it by then; but if it was a really difficult problem, or a seemingly lose-lose scenario, it landed on my desk… The first step to making those hard decisions is being comfortable with the fact that you’re not going to make a perfect decision – not all the time, maybe never; and understanding that you’re dealing with probabilities, so that you don’t get paralyzed trying to think that you’re going to actually solve it perfectly… Once I have all the information, and I’m confident that I understand the challenge, if I could get to 51 percent probability on a decision, having consumed all of the available information, then I would make that decision and be at peace with the fact that I had made the best decision I could with all the available information I had” (121).

- Paraphrasing the psychologist David Dunning, Bartlett writes, “Dumb people…see the world in black and white and make emotional decisions whereas smart people think in probabilities” (123).

- Don’t ask, “Will X or Y occur?”

- Instead ask, “What is the chance of X or Y occurring — 10, 50, 80 percent?” (123)

- “A 51 percent decision is enough to be at peace. Know that 100 percent doesn’t exist” (123).

Chapter Twelve

- “I’ve spent my life in high-pressure business situations where bad news is both unpredictable and frequent… Because of this, I’ve been able to develop an unwavering and dependable sense of calm in the most ferocious moments of disruption so it’s rare that anything moves me to the point that I can’t control my thoughts, reactions, and feelings” (124-125).

- “Composure really really matters” (125).

- “If you want to avoid making the same mistake twice, make more decisions based on your past memories and less decisions based on your current emotions” (127).

- “When someone cheats on or dumps us, or when we feel rejected in any context, it isn’t the action itself that harms us, it’s the stories we then subconsciously tell ourselves about ourselves because of the rejection that ultimately do all the damage. A deliberate act of rejection is a brutal assault on our self-esteem and our sense of self-worth” (128).

- “Our work, our talents, and our love are all crucial building blocks in the composition of our self-esteem” (129).

- “Sadly, those with low self-esteem go to great lengths to avoid the possibility of rejection. They habitually avoid promising opportunities, engage in self-disparaging behavior, and talk themselves out of the chance of romantic love” (129).

- “If you feel an urge to ‘win’, take revenge or protect your ego, then your rational mind is no longer in control. Do not listen. The best reaction in high-emotion, ego-wounding situations is nearly always no reaction” (131).

Chapter Thirteen

- “When you’re a leader and are delivering sensitive news to your team, it isn’t just what you say that your team — it’s how you say it… I was calm, confident, unemotional, and assertive” (137).

- “You’ll never prevent all chaos. But you can learn to find your calm in any chaos” (138).

- “Deep down, almost innately, I think I realize that anger, self-pity, and other potent emotions are nothing more than a distraction from solving the problem” (140).

- Looking back on the email hack, Bartlett reflects, “Although it wasn’t our fault, as CEO I still feel a great sense of responsibility” (142).

- “Reminding yourself that you have survived every moment of chaos that life has thrown at you so far, and you’re still here now, is a great indicator that you have what it takes to survive this too” (145).

- “If you want to feed a problem, keep thinking about it. If you want to starve a problem, take action” (145).

- “Optimism, proactivity, and focus — without those three things, I wouldn’t be here” (145).

- “Fundamentally we’re all the byproduct of not what has happened to us, but how we chose to handle it” (146).

Chapter Fourteen

- “The power of consistency over time is both profound and underrated. It’s profound because it’s the most common factor in the story of every ‘successful’ person I’ve ever met, but it’s underrated because it’s totally invisible” (149).

- “‘Be Consistent For a Long Time’ should be the title of every self-help book ever written” (150). But first, you have to find something worth being consistent at.

- Cf. Margaret Lobenstine’s The Renaissance Soul for advice on discovering and pursuing various interests and maybe moving on from them with time.

- “Therein lies a key factor of compounding efforts and consistency — time… The sooner you get started, the sooner you beging investing, learning, building experience and therefore creating invsibile momentum, the better. Time is everything” (154).

- “The Eighth Wonder of the World [Compound Interest] isn’t just working for or against your bank balance, it’s at work slowly, and virtually invisibly, shifting the trajectory of every aspect of your life: your health, your mental health, your reputation, your relationships — everything” (156).

- “[As the CEO of Social Chain,] I saw how a series of small, seemingly insignificant decisions that team members made gently furthered their reputation, trustworthiness, and eligibility for promotion, or how small and seemingly insignificant decisions did the opposite” (156).

- “Your reputation is a series of persuasive stories that line in other people’s minds” (156).

- “Reputation cares more about your fundamentals, your integrity, trustworthiness, morals, how you treat other people, and how accountable you are to your word” (157).

- “You, me, and everyone else reading this book has their own Invisible PR which is compounding for or against them right now. It’s built on every action and decision you make. It isn’t necessarily accurate, and it isn’t always true, but as it relates to Invisible PR, the truth doesn’t matter and perception is considered reality” (158).

- “Over the span of a decade or the course of a lifetime, your Invisible PR will have more influence over the trajectory and direction of your life than any other force” (158).

- “Focus neurotically on the small stuff. Value your integrity, trustworthiness, your morals, how you treat other people, and your word obsessively. Protect your Invisible PR like your life depends on it — because it does” (158).

- Refencing James Clear’s Atomic Habits, Bartlett writes, “Most people need consistency more than they need intensity. Intensity makes a good story. Consistency makes progress” (159).

- “You have to want your success enough and enjoy the process enough to be willing to believe in and work for it, potentially for years, without actually being able to see it compounding” (161).

- “Our small decisions are grossly underestimated, and our big decisions are typically overestimated” (161).

- “My success wasn’t the result of one great act; it was the result of many small, good acts, repeated over 10 years. Greatness isn’t one decision. Great is just good repeated, over and over again” (162).

Chapter Fifteen

- “Willpower depletion only exists for those who believe their willpower is depleting” (166).

- “Many psychologists now believe… that individuals can show extreme levels of self-control and willpower, so long as they believe their willpower to be a limitless resource” (168).

- “Labels are the short-cut, over-simplified descriptions we give ourselves, of ourselves. They are binary boxes that contain a series of implicit instruction on who you are and how you should behave” (168).

- “Once you’re inside a labelled box, the science says you’ll naturally start acting like he label written on the front of the box” (169).

- “I will not label myself, because for all its convenience, I know how limiting labels can become… I’m just a human with a bunch of skills, experience, and perspectives that I apply to challenges I believe to be worthwhile” (169).

- “Our beliefs are the by-product of the subjective evidence we have and our own interpretations of that evidence. If you want to uproot them, words alone aren’t enough; you have to expose yourself to new evidence that challenges them, that contradicts them and that categorically disproves them” (172).

- “Unfortunately, intention is nothing without action and action is nothing without intention. Progress happens when your intentions and actions become the same thing” (175).

- “Motivational words and positive intentions stand no chance against our psycholigcal hard wiring. No matter what motivational seminar, talk or course you attend, you’ll quickly return to your default psychological state if that motivational talk doesn’t inspire you to take action that ultimately leads you to create new evidence about who you are and what you’re capable of” (176).

- Cf. Michael Easter’s The Comfort Crisis and the concept of misogi. Challenges that expand your perception of your limits and capabilities.

- “One of the most valuable things you can do, for your mental health and your future, is to journal or keep a diary. It’s impossibly difficult for most of us to understand why we do the things we do just by thinking about it… [We need] the deep introspection that journaling inspires” (176-177).

- “If there is a single force in this world that is holding you back, it probably isn’t other people, your boss, the political party in charge, or even your circumstances; it is you, and the stories you believe about you” (177).

- Referencing Nir Eyal, Bartlett writes, “We’ll neve achieve our goals if we don’t fundamentally understand what psychological discomfort we’re trying to escape from” (180).

- “Growth is achieved by learning and unlearning at the same time. Reading books like this is a great way to learn. Reading yourself is a great way to unlearn” (180).

- “Money doesn’t corrupt you; it just gives the subconscious forces that run your life in the background with more resources to play with” (184).

- “Often the things that invalidated you when you were a child will be the things you seek validation from as an adult… It turns out that validation is an inside job — only you can validate you” (185).

- “The most convincing sign that someone is truly living their best life, is their lack of desire to show the world that they’re living their best life. Your best life won’t seek validation” (186).

Chapter Sixteen

- “This sentence structure, ‘X made me Y because of Z’, is one we’re all familiar with… I think it’s important to understand that any time you use this sentence structure, you’re lying to yourself and doing yourself a huge disservice at the same time. This sentence mitigates all the responsibility you have over your mood” (187-188).

- “Having control over your emotional responses means you can think, respond, and act with reason and clarity, and rational thinking is far more conducive to successful outcomes” (190).

- An internal locus of control is when “you believe that you have control and responsibility over what happens in your life” (191).

- An external locus of control is when “you believe that you have no control over what happens and that external variables are to blame” (191).

- “Your locus of control can influence not only how you respond to the vents that happen in your life, but also your motivation to take action when it matters the most” (191).

Chapter Seventeen

- “I’m not one of those superhuman robots that I often read about, one of those mythical super-entrepreneurs who springs up out of bed at 4am, drinks green juice, meditates, journals, and goes for a one-hour run every morning without fail… I’m disorganized. I don’t like getting out of bed and I don’t routinely meditate. If I don’t have an urgent meeting that I have to wake up for I won’t set an alarm… Sometimes I eat healthily and sometimes I eat shit; sometimes I’m disciplined and sometimes I struggle. My sleeping patterns are all over the place, usually determined by my schedule. I procrastinate. get distracted easily and spend too much time down internet rabbit holes” (197-198).

- “If the external pressure to be a ‘happy sexy millionaire’ is strong and your need for external validation is high, then your intrinsic desires stand no chance of being heard, pursued or achieved, and you will live your life genuinely believe that you want something you don’t actually want — something that won’t actually truly fulfil you” (200).

- “You must interrogate the logic, values and rationale behind your goals and ambitions as if your life depends on it — because it does” (200).

- Bartlett gives a short list of things you will regret:

- “Allowing your potential to remain trapped behind strangers’ opinions.

- Spending more time thinking about the past than living in the moment.

- Time spent with people that don’t want the best for you.

- Neglecting family.

- Never taking risks” (201).

- “It’s clearly so unbelievably important to know what you actually want, who you actually are, and to be able to tell the difference between the person the outside world wants you to be, and the person your inside world yearns to become” (202).

- Again, cf. Lobenstine’s “The Renaissance Soul.” She provides several exercises to help you discern your values, prioritize areas of life, and do the things that matter most to you.

- “I’ve never experience burnout when doing things I honestly enjoyed doing, regardless of how many hours I give to it” (203).

- “If you spend long enough pursuing those extrinsic goals, for extrinsic rewards, burnout seems somewhat inevitable” (203).

- Remembering his time in school, Bartlett writes, “I was never inherently lazy. I, like you, am just not interest in doing things, for long periods of time, that I’m not intrinsically motivated to do. When I am aligned with my inner dreams, I’m the hardest-working person on planet Earth” (205).

- “At the most fundamental level we all just want to be happy. We mistakenly think stuff, status, and external approval will get us there. But it’s the intrinsic things like friendship, internal fulfillment, and our honest passions that ultimately hold the key to happiness” (205, 207).

- “If someone pays you to do something you love doing, you’ll lose some of the motivation to do it” (207).

- In psychological terms, this is called the “undermining effect” and it states, “if you provide incentives for someone to carry out an activity they already enjoy, it undermines their original reason for doing it” (207).

- For example, I love reading and writing and learning in general. But if you slap me in a classroom, give me a reading list, tell me to write an essay, and attach a grade to it, I lose basically all of my intrinsic desire to read and write.

- “It is useful to think of motivation not as a binary concept, but a concept that lives on a continuum ranging from ‘non-self-determined’ (things you’re forced to do) to ‘self-determined’ (things you choose to do)” (208).

- The self-determination theory model identifies three basic needs:

- “Autonomy: people have a need to feel that they are the masters of their own destiny and that they have at least some control over their lives; most importantly, people have a need to feel that they are in control of their own behavior” (210).

- “Competence: people have a need to build their competence and develop mastery over tasks that are important to them” (210).

- “Connection: people need to have a sense of belonging and connectedness with others; each of us needs other people to some degree” (210).

- “If you want to motivate someone, be positive and constructive with your feedback… if your criticisms are geared towards constructive self-development, and not personal or ambiguous critique, then you’ll be fine” (212).

- “Those who have high feelings of personal responsibility — and believe that their actions determine their outcomes — are typically the most motivated, because if you don’t feel like you have control over the outcomes then, according to psychology, you’re less likely to have the motivation to do the task in question” (213).

- “It’s your job to fight back, to hear your internal voice through the noise and to make that voice the most influential one in your life. If you can, you’ll find happiness. Add a serving of responsibility, freedom and some feelings of competence and you’ll find motivation” (215-216).

Chapter Eighteen

- “I used to think that you had to be the best in the world at an individual skill in order to be the best in the world in your industry… However, the rest of our lives, careers and professional ambitions are multifaceted, and success doesn’t depend on mastering one skill” (219).

- Talking about skill stacking, Bartlett writes, “It’s actually easier and more effective to be in the top 10 percent in several different skills — your ‘stack’ — than it is to be in the top 1 percent in any one skill” (220).

- “To become the best in your industry you do not need to become the best at any one aspect, you just need to be very good at a variety of complementary skills — skills that your industry requires for personal success, The more unique the skills, the better” (220).

- For example, Bartlett was voted as the #1 leading figure in social media marketing and his skill stack focuses on social media marketing (the technical shit), business, personal branding, visionary leadership, public speaking, and sales (219, 221).

- “You need to build skills that not only work together, but are also diverse enough to make you uniquely valuable. Choose to build uniquely complementary skills that you don’t often see in the same person” (225).

- To help you build your unique skill stack, Bartlett asks three questions:

- “What skills do you currently have?

- In your industry, what skills do people usually have?

- Given that more people have these skills, what new skills could you learn that will give you a valuable edge over others within your industry?” (227)

- “If you are willing to step outside of your zone of comfort into territories that someone like you doesn’t usually explore, you too can build a skill stack capable of changing your life, eclipsing your industry and potentially even changing the world” (227).

Chapter Nineteen

- “No matter how hard we try, we’re stuck with an ever-diminishing amount of time” (228).

- Approximately 500,000 hours, if you live for 80 years and actually sleep some of it.

- “How we place these 500,000 chips [hours] will be the single biggest determining factor of our outcomes: our success, happiness, safety, legacy, intellectual development, and mental well-being. These 500,000 chips are all we fundamentally have” (228-229).

- “We don’t seem to live as if time is all we have and that the time we have is limited… We live in a culture that does its best to deny the reality of death… We don’t have the emotional fortitude to embrace the fact that it will happen to us” (229).

- “In a world where your sand time sits in front of you at all times, every choice you make or don’t make is a visible sacrifice” (231).

- “How should we live given that life is short, and time is running out on us?” (232)

- “Start by becoming crystal clear about the things, ambitions and goals you deeply value above all else” (235)

- “In order to ensure that these values are intrinsic, interrogate them relentlessly and as if your life depended on it. Demand to know the source of them, the reason for them and get clear about why those things matter to you” (235).

- “Your intrinsic values should exist — by definition — free from the influence of external judgement” (235).

- “The goal is to place your chips with intention, as best as you can, today and to repeat that every day… When your currency is limited — like your time — your pending habits need to be policed meticulously; you need to budget, prioritize and be frugal” (236).

- In most areas of life, like money and love, it may be good to have an abundance mindset. But when it comes to time, you want a scarcity mindset. Because you time is fundamentally limited.

- “In a practical sense, the more difficult yet equally important challenge is learning to say ‘no’ — even when it’s something you want to do” (236).

- “The more successful I became, the more people and opportunities demanded my chips and the more ruthless I had to become in placing them. It turns out this strict focus makes you even more successful, which increases the demand on your chips and the cycle continues” (238).

- “I should have avoided time-consuming, low-return tasks and said ‘no’ as much as possible” (240).

- “It’s my sole responsibility to defend, protect and conserve my time. Nothing matters more, and my time is all I have” (241).

- On the flip side of being intentional with your time, be extremely grateful of the time others spend with you. It’s the only time they have and they’re choosing to spend it with you. That’s fucking miraculous.

- Concerning outsourcing, Bartlett adds, “It means I’m able to save time on things that I don’t truly value to spend more time on the things I do” (242).

- “It’s also the most important philosophy behind being happy and successful — spending your time doing what you love, and one what you believe matters” (242).

- “How you choose to spend your time is probably the center point in your circle of influence. therefore changing what you spend your time on ca indisputable change your life more than any other single behavioral change” (242).

- “If you were able to protect your time a little better, become a little more intentional in how you place your chips on the roulette table of your life and develop more clarity on the things that hold long-term, intrinsic value to you, then you probably wouldn’t need to read anther self-help personal-development book in your life” (242).

- “Time is both free and priceless” (242).

- “The person you are now is a consequence of how you used your time in the past. The person you’ll become in the future is a consequence of how you use your time in the present. Spend your time wisely, gamble it intrinsically and save it diligently” (242).

Chapter Twenty

- “It was the realization that I was already enough that opened the door to a level of gratitude that had escaped me for my entire life” (246).

- “It was freeing myself from these extrinsic distractions and zero-sum games, that made me more successful” (246).

- “It was that stability, and the lack of external validation, that led me to real love” (246).

- “You are you, and you will always be that. Your life doesn’t have varying and fluctuating levels of inherent value… You’re never be intrinsically defined, valued or measured by your car, bank balance, job title, followers or accomplishments” (248).

- “REAL ambition is not based on or inspired by the desire to be ‘more’ than you are… Real ambition is about you; it doesn’t care about likes, followers or comments, it cares about what honestly matters to you” (248).

- “It’s realizing that you are enough that creates the real genuine ambition to pursue your greatest internal goals, for the sake of nothing more than fulfillment, satisfaction, and enjoyment” (248).

- “Knowing that you are already enough will give you the focus, genuine motivation, and, therefore, the consistency that you will need to pursue the things that genuinely matter to you, for your own reasons… it’s the pursuit of those things, not even the attainment of them, that will give you the happiness we’re all so desperately ‘searching’ for” (250).

Source(s)

- Happy, Sexy Millionaire by Steven Bartlett

Cross-Reference(s)

- Kahneman Thinking, Fast and Slow

- Schwartz The Paradox of Choice

- McKeown Essentialism

- Godin The Dip: A Little Book that Teaches You When to Quit

- Lobenstine The Renaissance Soul

- Kaufman The First 20 Hours

- Clear Atomic Habits

- Bartlett The Diary of a CEO podcast