For the month of April 2020, I’m experimenting with my nutrition. I want to avoid heavily or ultra-processed foods in my diet. To do that, I’m cooking more and buying less ultra-processed, prepared foods and ingredients. I am also taking an online course to help me learn to cook. The course is titled “The Everyday Gourmet: Rediscovering the Lost Art of Cooking.” It’s offered by The Great Courses and is taught by Chef Bill Briwa, who was a chef at The Culinary Institute of America. Thankfully, the course is available on a streaming platform named Kanopy, which Swarthmore College makes available to students. Otherwise, it’s available for purchase directly from The Great Courses.

In February 2020, I tracked all of my consumption for the month. You can check out the launch and summary posts for that experiment. For March, I didn’t track or complete a nutrition experiment. Now, for April, I’m back for another experiment.

Background

At times in my life, I have assumed that I could not eat “healthily” because “healthy food” was too expensive for my budget. While I’m positive that you can spend a lot of money eating healthily, my wife and I don’t make a lot of money; we’re on a budget. For us, that means we spend up to $100 on food per week. I know that, depending on where you live, $100 per week for food for two people may seem surprisingly high or laughably low. Context is important.

Also, I think it’s important to note that my wife is not joining me in this experiment. That’s fine. Her nutritional goals and methods are different from mine. This just means that I cannot completely eliminate heavily processed foods from my environment, a method called environment design. Matt D’Avella talks about it in his video, “3 Ways to Make Your Habits Stick.” Since we shop together, this experiment will influence the groceries we buy, but if she wants a processed snack food, that’s perfectly okay. Since I tend to cook (though she often helps), we’ll both eat fewer (or no) processed foods in our main meals each day.

While I am taking a course to improve my cooking, I am not new to cooking. I began cooking when I was 13-14 years old. More relevantly, I’ve been cooking 2-3 meals per day for myself and my wife since we moved in together in May 2019. This project would be much more difficult if I expected myself to learn to cook and to cook 3 meals per day on the first day of this experiment.

Lastly, we’re staying at home for the entire month of April because of the coronavirus pandemic. Our county is under stay-at-home orders, her job is closed at least until early May, and I’ve been working from home the last few months since I’m taking a leave of absence from college this semester. This experiment would likely be smaller in scale if I were attending classes right now and not at home all day. You could begin with eating one home-cooked meal made with minimally processed ingredients if cooking three meals per day is a daunting change.

Before I delve into the details of the experiment, let’s address the looming question.

What is heavily processed food?

I think it’s impractical to avoid processed food entirely when you live in a metropolitan or suburban town in a highly-developed economy like the U.S. Esther Ellis of EatRight.org defines processed food as, “… food that has been cooked, canned, frozen, packaged or changed in nutritional composition with fortifying, preserving or preparing in different ways. Any time we cook, bake or prepare food, we’re processing food.” This does not mean that processed food is universally bad.

Problems arise from what I am calling “heavily processed foods.” There isn’t a clear line that distinguishes minimally processed from heavily processed foods, but high levels of processing generally occur when food undergoes chemical processing. Andrew Wilder of EatingRules.com applies a “kitchen test” to determine if a food is unprocessed or processed. It reads, “Unprocessed food is any food that could be made by a person with reasonable skill in a home kitchen with whole-food ingredients.” When the kitchen test determines a food is “processed,” I tend to consider that food heavily processed. Below, I provide examples of processed and heavily processed foods I am exchanging for unprocessed or minimally processed alternatives. Let’s dive into the details of the experiment.

Experiment

Tracking

At the end of the summary post for my February 2020 experiment, I listed several changes I want to make to my nutrition. I said,

“I am unsatisfied with the current status of my nutrition and I want to change the following,

- Satiety. I don’t like eating and always feeling hungry immediately after my meal.

- Energy. I want to have more energy throughout the day.

- Body Fat Percentage. BMI and WHR are helpful, but BF% is the metric I find directly related to my perception of my health. It has decreased significantly since the beginning of February, but I’d like to slowly get it into the 10-11% range.

- Environmental Footprint. I want to reduce my footprint via my food choice, its source, and its packaging.

- Engagement with Food. I want to promote a positive relationship with food, including my buying, growing, preparing, and eating experiences.”

My April 2020 experiment is primarily concerned with the fifth point, Engagement with Food. Since I’ll be cooking more and paying more attention to my food choices, I hope to improve my engagement with food. I don’t know if/how to measure this engagement in a quantitative way, though. I will be measuring the number of heavily processed items I eat in a day, but I won’t be measuring every un- or minimally processed food I eat.

I’ll see how the experiment affects the other four points, too. I expect to improve my environmental footprint while choosing foods that undergo less processing and might be organic, Fairtrade, grass-fed/-finished, free-range, and/or produced by a B Corp. I won’t be tracking to measure my environmental footprint during this experiment, though. If you have thoughts on a quantitative way to measure the environmental footprint of food choices, I’d love to hear them.

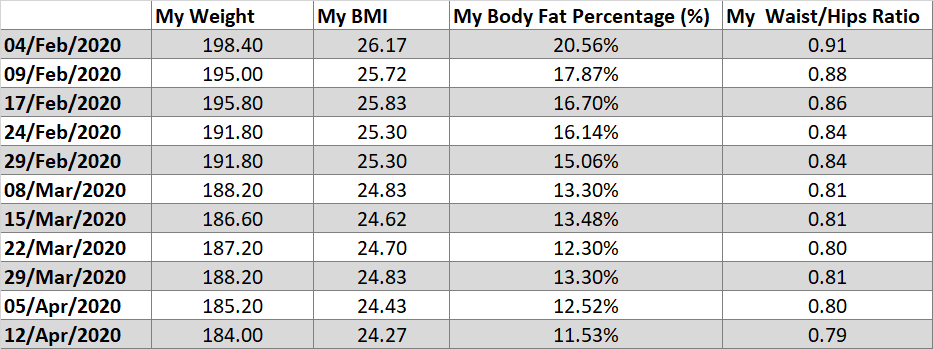

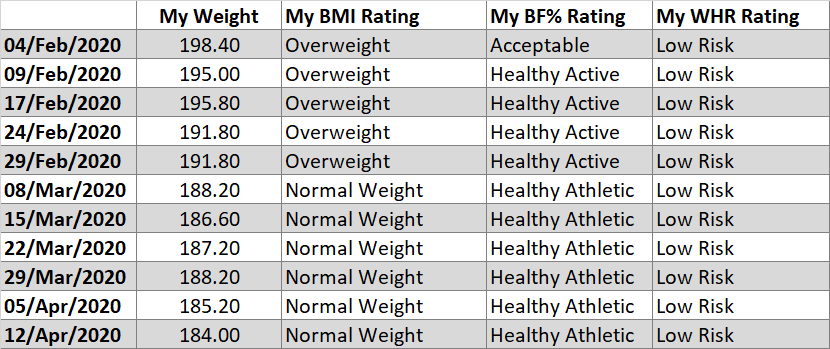

I continue to measure my body fat percentage (and other measurements) on a weekly basis. You can see my numbers for February and March below; I’ll include my numbers for April when I write the summary post for this project. If you want to read about the measurements I track, see the launch post for my February 2020 experiment.

I will not be quantitatively tracking my energy or satiety during this project, but I will qualitatively track these factors during the experiment. Basically, I may ask myself two questions every evening: “How was my energy today?” and “How was my satiety today?” At the end of the month, I’ll see if there were any trends in the qualitative data.

So, beyond “cooking more” and “avoiding heavily processed foods,” how do I intend to perform this experiment? What am I changing in my daily life?

Changes in Food Choice

If you want to replicate this study, the changes you make to your daily life will definitely be different. Additional changes will become apparent as I proceed with the experiment, but some changes I already anticipate making include,

- Use brown rice instead of white rice (red and forbidden rice are good options, too). My wife and I normally each eat half a cup (dry) of rice with supper daily.

- Use steel-cut oats instead of instant or rolled/traditional oats. I eat half a cup (dry) of oatmeal every morning with breakfast.

- Buy organic, grass-fed/pasture-raised milk, cream, butter, and any other dairy products.

- Buy organic, free-range eggs.

- Use flour that is unbleached and unenriched.

- Use unrefined, extra virgin, cold-pressed, expeller-pressed, and other minimally or unprocessed oils.

- Buy organic, grass-fed/pasture-raised ruminant meats and organic, free-range/pasture-raised whole chickens.

- Buy chocolate made without soy lecithin and alkali.

- Stop consumption of frozen pizzas, boxed macaroni & cheese, and other prepared or almost-entirely prepared meals.

Exceptions

There are exceptions to every rule. While I am changing many of the foods I eat on a daily basis, I am not changing some common foods and ingredients. Among these are,

- Corn starch. We primarily use it in sauces and my wife’s homemade hot chocolate. I may try arrowroot powder, but I think we’ll continue using corn starch.

- Baking soda and baking powder. I’m currently unaware of substitutes for these two ingredients when baking. I may find something, but I generally consider the “pro” of homemade bread and other baked goods to outweigh the “con” of these two heavily processed ingredients.

- Whey protein powder. I use a verified low-toxicity, rBST-free whey protein powder on a daily basis. I know it’s heavily processed and I consider this my one big cheat food during this experiment, but I think it’s a big “pro” in my daily diet because I otherwise don’t eat enough protein and it’s a tasty reward that reinforces a healthy habit, my exercise routine.

Goals

My goal for this experiment is to improve my engagement with food by learning to cook, cooking more, and being more mindful about my shopping and consumption. I also hope to improve my energy, satiety, body fat percentage, and environmental footprint via these dietary choices, but I do not expect these improvements as outcomes of the experiment. I’ll be back in early May with a summary of the experiment. Until then.

[Edit 12 April 2020.

Sorry, folks. I said I’d add my measurements, but forgot to. Here they are. I track my weight in pounds, waist in inches, and hips in inches every week, then calculate my BMI, Body Fat Percentage, and Waist/Hip ratio. I use formulas and ratings available on bmi-calculator.net.

Measurements

Figure 1: Measurement Numbers

Figure 2: Measurement Ratings

End of edit.]

Resources

- The cooking course I am taking, taught by Chef Bill Briwa of The Culinary Institute of America.

- Kanopy is a streaming platform that Swarthmore College makes available to students. It’s popular among libraries and universities, so see if your local institutions offer it!

- The Launch Post and Summary Post for my February 2020 Wellness Project.

- Matt D’Avella has many wonderful videos on nutrition, habits, and experiments. His video on improving habit retention is helpful and mentioned above.

- Here’s a Healthline article on 15 foods that rank high on the satiety index.

- Another Healthline article, this one talks about rice.

- Esther Ellis wrote a helpful, introductory article on eatright.org that explains the good and the bad in processed foods.

- A WebMD slideshow that also shares helpful information on processed foods and ultra-processed foods, including key factors to avoid: added sodium, added sugars, and trans fat.

- Grant Tinsley wrote a helpful Healthline article on whey isolate, whey concentrate, and casein protein supplements. For the purposes of my experiment, the article discusses how whey protein supplements are processed.

- The Clean Label Project tested dozens of protein supplements from top brands for the presence of over 100 toxins and contaminants. My supplement ranks 5 stars. When buying supplements, I think it’s extra important to pay attention to quality.

- Here’s an article from Eating Rules that talks about processing in meat and eggs. Eating Rules has another article on flour and grains.

- Eating Rules also has an article talking about oats. As an everyday oatmeal eater, I enjoyed the post. I use to eat old-fashioned oats because steel-cut oats were hard to find in stores. Then I found a smaller grocer than sells steel-cut oats in bulk, so I’ve been loving those for the last few months.

- Eating Rules’ Kitchen Test.

- A helpful Time article on various oils. It doesn’t go into much detail on any one oil but provides a quick overview of about a dozen different oils.

- The featured image is by Louis Mornaud on Unsplash.

2 Replies to “Project Launch: Avoiding Heavily Processed Foods”

Comments are closed.