April is over and I concluded my latest project, “Avoiding Heavily Processed Foods.” The results were mixed. If you want to know the background for this project, check out the launch post. In that post, I detail how I define “unprocessed,” some of the science behind why heavily processed food is “bad,” what I’m tracking and how, and my goals for the project. After you’ve read that, come back here and we’ll jump into my summary of the project!

Brief Recap on Launch Post

For the month of April 2020, I avoided eating heavily processed foods. To do this, I tracked the heavily processed foods I ate and I cooked every meal at home basically every day. I described “heavily processed food” as any food or ingredient that cannot be made by a person with reasonable skill in a home kitchen with whole-food ingredients. Finally, I made a few exceptions for this experiment by allowing myself to use cornstarch, baking soda, baking powder, and a low-toxicity whey protein powder.

To improve my cooking skills, I completed an online course by Chef Bill Briwa titled, “The Everyday Gourmet: Rediscovering the Lost Art of Cooking.” I took notes on the course, practiced cooking, and wrote about several lessons from the course in the Daily Learning category/series.

I tracked the heavily processed foods I ate each day, my perception of my energy and satiety each day (beginning 12 April 2020), and several health metrics, such as weight, body fat percentage, and body mass index (BMI). I tracked these health metrics once per week.

My main goal for the project was to improve my engagement with food “by learning to cook, cooking more, and being more mindful about my shopping and consumption.”

In addition to the main goal, I was curious to see if the experiment improved my energy, satiety, body fat percentage, or environmental footprint. I did not track my environmental footprint, but I qualitatively tracked my energy and satiety and I quantitatively tracked my body fat percentage.

With that brief recap, let’s see my results.

Results of Avoiding Heavily Processed Food

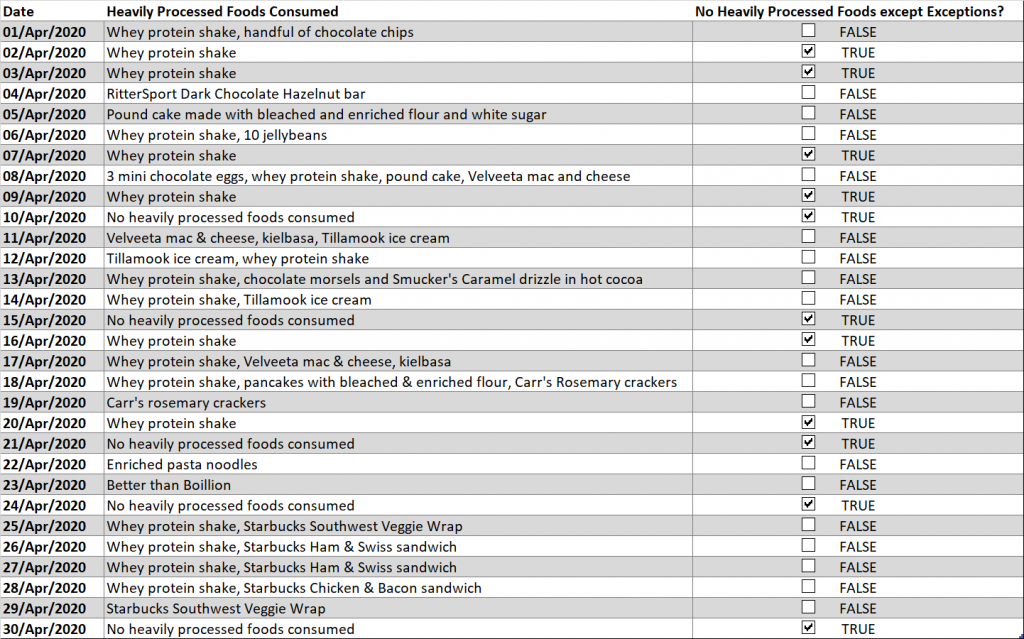

My performance was far from perfect during this experiment, and that’s okay. There were only 5 days in April where I only consumed unprocessed and minimally processed foods. That’s only approximately 17%. If you include the exception I made for a daily whey protein shake, then I “passed” on 11 days, or approximately 37% of the days. The other 19 days of the month, I ate at least one heavily processed food or ingredient.

Figure 1: Heavily Processed Food Consumed

Energy and Satiety

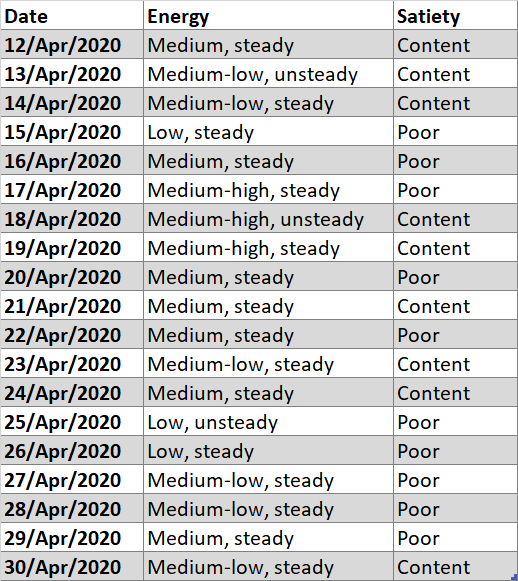

Partway into the month, I decided to qualitatively track my energy and satiety each day. At the end of each day, I asked myself “How was my energy today?” and “How was my satiety today?” I hoped to see a definitive trend because of my dietary change, but I did not.

My energy was better during most of the experiment. I am, however, beginning to think that has more to do with the amount of sleep I received during most of quarantine. In the last few days of April, my wife returned to work and we slept less. My energy plummeted during those last few days of the month, even compared to how I felt on the “medium-low” days of quarantine. Therefore, I’m inclined to blame sleep for my energy more so than this dietary experiment.

My satiety definitely improved overall, though. While I wasn’t tracking satiety prior to the experiment, I would say that I was rarely content with my satiety in March 2020. My satiety swung (and still swings) from day to day, but it improved while eating minimally processed foods.

Figure 2: Tracking Energy and Satiety

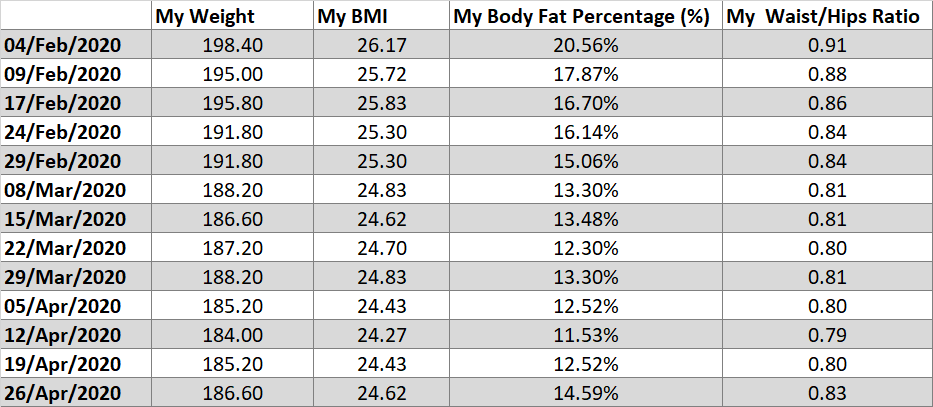

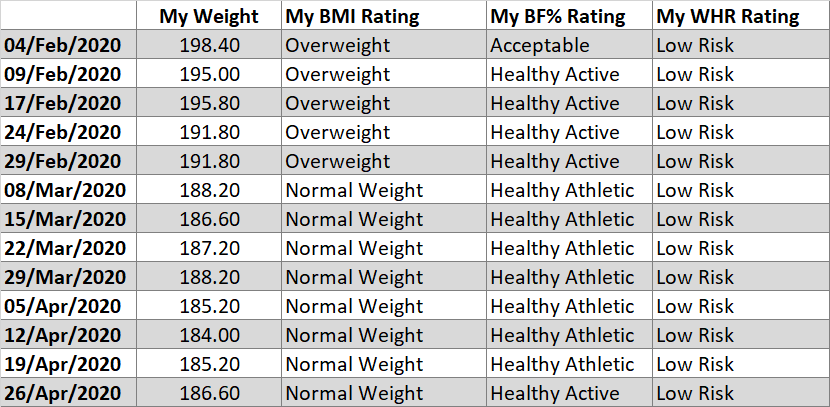

Finally, I tracked my weight (lbs), waist (in), and hips (in) each week. Using these numbers, I calculated and rated my BMI, Body Fat Percentage, and Waist/Hip Ratio. Looking at my measurements, this experiment did not affect my body fat percentage in any significant way.

Figure 3: Measurement Numbers

Figure 4: Measurement Ratings

Engagement with Food

I think the clearest improvement was in my engagement with food. I thoroughly enjoyed Chef Bill Briwa’s course, “Rediscovering the Lost Art of Cooking.” Learning from Chef Briwa has made me more confident, knowledgeable, and creative in the kitchen. While I’m far from a master chef, I find myself enjoying the time I spend in the kitchen and appreciating the tools and foods I work with. I think learning to cook at a basic level may be an essential and enriching skill, especially for those who are concerned about the food they eat and how it’s prepared.

While I have not affiliation with The Great Courses, I’m glad they teamed up with Chef Briwa to make this course. Furthermore, I’m grateful that Swarthmore College makes many of The Great Courses available via its subscription to the streaming platform Kanopy. Sadly, due to recent circumstances, that subscription is ending.

Finally, I want to end this post with a sample meal plan.

Sample Meal Plan while Avoiding Heavily Processed Food

Sometimes it’s difficult to visualize what you might eat in a day on a specific diet. Therefore, I want to share an example of what I commonly ate in a day while avoiding heavily processed foods.

Typical Breakfast

- 4 ounces of steel-cut oats cooked with .5 cup blueberries and cinnamon.

- 1 small-medium apple, sliced.

- 2 tablespoons peanut butter.

Typical Snack

- 8-ounce protein shake made with organic, whole milk.

- 12 ounces coffee with cream.

Typical Lunch

- 4 ounces of French lentils cooked in water, possibly with rosemary or thyme. Tossed with salt, pepper, and 2 tablespoons of organic, extra virgin olive oil.

- 2 eggs cooked however you like.

Typical Supper

- 4 ounces of brown rice.

- 4-6 ounces of meat. Sautéed, roasted, or cooked into a dish.

- 1-2 cups of vegetables. Roasted, steamed, boiled, or cooked into a dish.

I think these typical meals worked well for me throughout the experiment. With a little more money in our weekly budget, I’d love to make several changes to the meals, though. Nevertheless, I think it’s insightful that my wife and I were able to eat healthily and well on approximately $100/week. Of course, depending on where you live, $100 per week for groceries for two people may be absurdly high or laughably low. Adjust accordingly.

The featured image is by Lily Banse on Unsplash.